The War Years

I was was born in Upminster, Essex, on the 27th September 1937 at 135 Sunnyside Gardens in the front upstairs bedroom. In those days, you gave birth at home with only a midwife present, almost always without any pain relief. If there was a problem you called the doctor. Many mothers died in childbirth in those days, so it was survival of the fittest.

Two years later the second world war started, so my first memories are of that era.

Upminster was a residential town to the east of London. About half the population worked in London in Banking and Insurance as the financial district was within easy commuting distance using the steam train to Fenchurch Street or the District Line which was part of the London Underground. Upminster was not a target for the German bombers who came over in great numbers during the Blitz, although Hornchurch Aerodrome was a key fighter station during the Battle of Britain and was only two miles away from our house.

My father worked in the London Docks as a carpenter-joiner at the time and as this was considered to be an essential job, he was not called up into the armed forces. He didn't have it easy though, as men in his position were expected to join the Home Guard and be ready to fight in the event of an invasion, which was a real threat at that time. Later during the heaviest months of the bombing, as well doing their 48 hour-week day job, men had to do fire watch in the evenings and nights with a bucket of sand and a stirrup pump to put out incendiary bombs dropped during raids( to cause as many fires as possible.)

We had an Anderson shelter in the garden (see photo below) where we went when the air raid siren sounded to let the town know that an air raid was imminent. These shelters were half underground and constructed of corrugated iron sheets which had a straight bit for the walls and curved at the top for the roof. They were bolted together and then covered in earth. They were cheap and quick to put up and were very effective. When a bomb exploded. Injuries were caused by the blast and from flying or falling brickwork and glass, so inside this shelter one was relatively safe. The only problem was that most raids were at night so you had to be woken up, put dressing gown and slippers on, go down the garden into a damp, unheated shelter, huddle there for an hour until the all-clear, then back to bed again, only to be woken up an hour later by the siren. People began to be so fed-up with this routine that they preferred to stay in their own beds and take the risk of being bombed. They adopted the frontline soldiers attitude of "if there is a bullet with my name on it, there is nothing I can do about it" In their case it was a bomb with their name on it.

One night my dad was out on duty and there was a raid. We did not go down to the shelter, but huddled under the dining room table which was of solid oak. Probably not much protection, but served its purpose. As the bombs fell we could hear the whistle they made. My mum knew they were bombs and was scared, so to reassure her, I said that the whistling noise was the sound of the tracer bullets that the anti aircraft gunners used to shoot at the bomber planes. I really believed what I said. Such was the innocence of a small child who knew only a state of war.I had no fear. Looking back when I was a parent with small children, I could only imagine what my parents must have felt like!

My bedroom was upstairs at the back and one day as I looked out of the window, I saw a german fighter plane, probably a Me 109, flying at roof top level.(see photo below) It was so close that I could see the pilot's helmet and goggles. I was convinced that he had seen me and would turn round and shoot me, so I hid under my bed. I read later that these were known as "scalded cat raids". The luftwaffe would send one or two fighter planes over the south of England to see how quickly the RAF would respond and send up planes to intercept them. At that point they were not aware of Britain's radar system. I was probably only about 4 at this time.

When the bombing of London started in earnest, we were evacuated voluntarily to Cheltenham in Gloucestershire. Uncle Bob Allsop was a cattle farmer and used to go there on cattle market days so he found some lodgings for us. I went with Mum, aunty Ivy and Brian, my cousin who was about 5 years older than me. I can vaguely remember going up a hill in a push chair and playing in the back yard of the house we stayed in, being pushed in a wooden cart by cousin Brian. We didn't stay there long as Dad and Uncle Bob had to work near London and I suppose Mum and Ivy got lonely.

Upminster was not a target, but was on the route from the french luftwaffe bases to the East End of London so the bombers had to pass over. One night 13 bombs fell on Upminster, which was unusual. Probably the bomber was damaged and dropped his bomb load before turning back.

Next day I saw a shop along Corbets Tye Road that had a flat above it. The front was demolished and the inside full of rubble. What registered in my young brain was a bed that had slid down the pile of bricks and I wondered if anyone had been in it.

We continued to go to school every day, with classes occasionally interrupted by the siren when we had to go to the shelters. These were concrete blockhouses in the playground.

The really heavy bombing of London only lasted a few months in which was called "The Battle of Britain" which was the prelude to an invasion of England. The German strategy was to wear down the Royal Air Force and defeat them so that the seaborne invasion could succeed, but the RAF were not overwhelmed and so Hitler abandoned the idea and turned on Russia instead.

The Luftwaffe continued to bomb at night so we had to suffer the constant irritation, but once we knew that an invasion was out of the question, people just got on with their lives. The motto was "grin and bear it" At the height of the Blitz, as it was known, 30 thousand people were made homeless every night, and yet next day the people of London went about their business as usual having to walk over the rubble to get to work. Nobody complained and their cockney humour prevailed. It made me smile when the London terrorist bombing ocurred and the hysterical reaction that followed. It is just what the terrorists want. The older generation weren't fazed by it at all as we all remembered hundreds of such tragedies on a daily basis and we lived through it without suffering "post traumatic stress disorder" either.

The next phase started in 1944 when Hitler started launching the V1 bombs on London. These were pilotless aircraft loaded with 1000kg of high explosive and rocket propelled.(see photo below) They were not accurate, but they had a calculated amount of fuel so when it ran out the bomb just glided down and exploded. They were faster than our Spitfires and Hurricanes so couldn't be shot down. Anti-aircraft fire was also ineffective and many got through. The only saving grace was that they made such an awful noise and when it suddenly stopped you just made sure that you were under cover. I can remember seeing one occasionally as it went overhead on its way to London. One night, one of them fell on Sunnyside Gardens about 500 yards up the road. We lost quite a few windows and roof tiles with the blast. We decided on another evacuation and so went to stay in Penarth, near Cardiff, to stay with some relatives. My mum and I only stayed 3 months. I was 7 and went to the local school where I remember having to do welsh lessons. I think the local boys thought I was an alien with my London accent among the soft spoken Welsh.

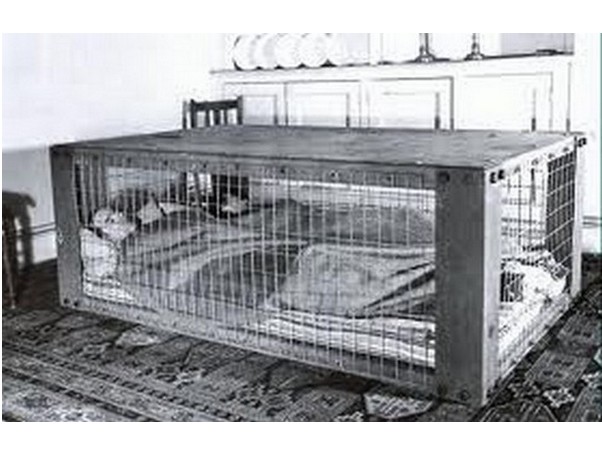

By this time we had a Morrison air raid shelter, named after Herbert Morrison, a Cabinet Minister. This was a sheet steel box with thick wire mesh sides.(see photo below) We set it up in the front downstairs room and Mum, Dad and I slept in it. I think that it was a very good idea. By this time the government realised that people were not using the shelters in the garden, preferring to leave their fate to God. Also they had discovered by then that when a bomb hit a row of houses most casualties were caused by the neighbouring houses collapsing, so if your house fell in you were safe inside your "box" and within a few hours the rescue services had dug you out. It never happened to me, luckily, but I think the idea was good.

One night we were asleep when something woke us up. Mum asked dad if there was a window open as there was draught. Dad got up and started to crunch around with glass on the floor. Most of our windows were blown out and we hadn't heard a thing. This was quite common when close to the centre of an exploding bomb. In this case it was a V2 rocket that had fallen, luckily, in a field nearby. (see photo below) The clay soil had also limited its explosive power. Next day we were in the field to examine the still warm crater and look for schrapnel. All little boys collected schrapnel, the bits of jagged metal that littered everywhere. Most was from the exploding shells of the anti-aircraft guns. I got a nice big piece from the rocket after a search.

The V2 rocket was a real terror weapon. There was no defence and it landed anywhere without warning. Luckily Hitler had only been able to develop it towards the end of the war. It had a limited range and the launching sites were eventually over-run by the advancing British and American troops. I believe most were in Holland and Northern Germany. It is interesting to note that the German scientists who developed these rockets had the choice of surrendering to either the Russians or the Americans. They chose the latter and were taken to the US where they were treated well and put to work on rocket development. Werner von Braun was famous and without his work, the Americans would not have been able to put a man on the moon. Once again the demands of war spur on developments that are then used to advance our civilisation. Satellites that are so common and essential to modern communications would not have been possible without von Braun's initial research and ideas.

I suppose that it is something to have had one land about 500 yards away and survive. Tony Clarke, later to become a friend, was trapped in his bed by a falling rafter as the rocket landed in the field at the bottom of his garden.

After D-Day which was on the 6th June 1944,in which about a million Americans took part, wounded soldiers were brought back to England to recuperate. The American government started a scheme whereby walking wounded were farmed out to live with British families until they were fit enough to be sent back to fight. As the money paid was good, we decided to have an American. The afternoon that he arrived I went for a walk with him to show him around. I was 7 or 8 at the time. As we went past the corner shop he asked if I wanted to buy an ice cream, for me an extreme luxury. He pulled out a handful of change from his pocket. I had never seen so much money before in someone's hand. Take what you want he said, I still can't understand your money!

Before the invasion we stayed at Uncle Vin's farm at Hatfield Peverel near Chelmsford and went for a walk along the country lanes nearby. All of a sudden we came across several American tanks parked on the side of the road and hidden from aerial view by the overhanging trees. As a young boy I was fascinated and we stopped to say hallo to the Americans. One of the tank commanders allowed me to climb up to the turret and lowered me inside the tank. I didn't know at the time, but I suppose it was a Sherman Tank. Most of the British Armoured Corps used the Sherman as well and they were no match for the German Tiger with its 88mm gun using armour piercing shells, but the Battle for Normandy was won because of the inexhaustable supply of replacements the Allies had. It was a battle of attrition more than skill and strategy.

It was also in 1944 that I had my tonsils out at Oldchurch Hospital, near Hornchurch. This was quite frightening for a 7 year old, as it was during wartime, times and the people were tough, and I was all alone as my parents were not allowed to visit. I was in an adults ward, but in the next bed was a lad who was having his nose syringed, I suppose because of blocked sinuses. I remember him coming back to his bed, holding a blood stained rag to his nose, which I did not find encouraging. The next morning a nurse came and gave me an enema. She gave me no explanation just turned me over and that was that. I didn't even know the word, but I can still remember the indignity of it. They took me to the operating theatre and put this horrible rubber mask over my mouth and nose and I struggled until passing out. As I woke up I was having a terrible nightmare.

When our son needed the same operation as a 2 year old in Venezuela, bearing in mind my own frightening experience, he was in Jenny's arms while they gave him an injection, then they waited until he was out before wheeling him away. When he woke up he was in bed in his room at the clinic with his mother beside him.

Later as a teenager when I needed to have a tooth out, I was offered an injection or gas. I chose gas just to expunge the terror I had felt as a little boy. By repeating the experience when I had a choice and some control over the situation, certainly helped. I awoke to a pretty nurse saying "wake up Mr Chapman" I groggily told her that I didn't have a bad dream that time. She said "That's good" in the tone of voice one uses when talking to an idiot.