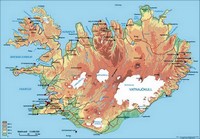

BSES Expedition to Iceland 1956

The British Schools Exploring Society had been sending schoolboys on expeditions for many years and occasionally one or two from the Royal Liberty School. In 1956 six of us applied from school and to everyone's surprise all six of us were accepted for the 1956 Expedition to Iceland. This was a record for the BSES also, as they selected boys from all the best public and grammar schools and in my opinion was a great credit to the teachers at the Royal Liberty School and especially to the Headmaster Mr.Newth.

We travelled on the 30th July from London's Kings Cross Station to Edinburgh, a 385 mile journey on the recently inaugurated express train service The Elizabethan. returning 7 weeks later on The Flying Scotsman, both famous trains in those days, and when my dad met me on the platform his eyes were wide with wonder as he had wanted to ride on this train when a young boy. The fact is that even today no train goes as fast as those old express steam locomotives. (They can, but the tracks will not take it).

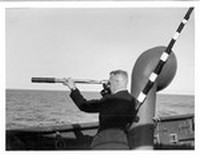

We went on board M.S.Gullfoss at 4.30 and sailed from Leith at 7.00 pm.

My diary entry reads Shown to scrubby quarters in smelly part of ship. There were 50 boys and 10 leaders so they had rigged up a section of bunks for us to sleep in. The leaders had cabins.

The next day was quite rough and I took to my bunk with an attack of sea-sickness. The following day was a lot calmer and we were able to play about on deck.

We docked at Reykjavik before dawn and disembarked at 9.30 am where we waited for some Icelandic dignatory to arrive, but he cancelled, so we set off in buses to the foot of the Langjokull glacier, where we would establish our base camp. On the way we stopped at the beautiful Gullfoss waterfall, one of Iceland's most famous sights.

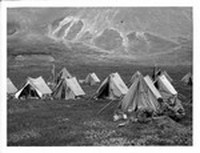

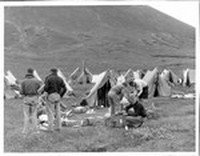

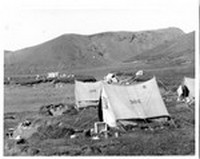

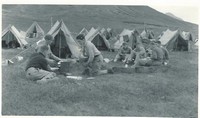

When we arrived at the camp we found that an advance party had already put up the tents for us so we spent the remainder of the day digging latrines and settling in. As it was mid-summer there was only a few hours of darkness so we were able to settle in without any trouble.

The location of our base camp was south-east of the foot of the Langjokull glacier. The GPS coordinates of the site were Latitude 64° 27' N and Longitude 20° 15'W.

The leaders were all serving or ex officers from the armed forces and most had

been members of previous expeditions. Doctor Porter who looked after our health and

Mr Ian Ashwell from the Meteorological Office were civilian leaders. The chief leader

was Major Hannell an ex WW2 veteran and professor of geography at Bristol University. His deputy Major Woods was also a WW2 veteran.

The boys were all from Grammar and Public schools and there was a good social mix, a

Baronet, a boy from Eton another from Ampleforth, I remember, with the majority grammar school boys

from working class backgrounds, but all with A levels and places at university waiting for them.

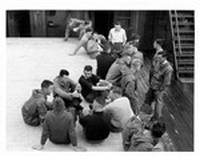

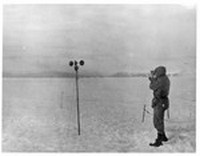

We were divided into groups or 'fires' according to our interests. There were geology, biology, surveying, wireless and meteorological groups. As the climate in Iceland at that time was a new research area, Dr.Ian Ashwell from the Meteorological Office joined us on the expedition with sets of appropiate measuring gear. He and Major Hannell wrote a scientific paper which they published later

The aim of the expedition was to give us a physically tough 6 weeks in the 'outward bound'

style and at the same time carry out useful studies that would be handed to the Icelandic

government as a favour in return for letting us tramp around their rugged country.

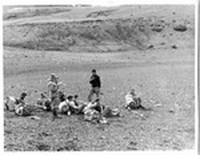

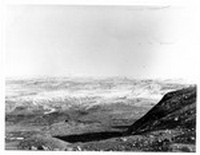

Iceland is a volcanic island and has very little vegetation in the interior. The ground is volcanic lava

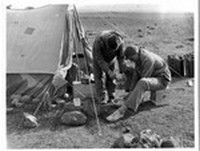

covered in small boulders and dust. We relied on parafin primus stoves for cooking and if we ran out

of fuel or they broke down (as happened on one march I was on) we had no cooked food as there were no

bushes or wood to make a fire. The crew of the US Apollo 11 moon landings, trained in Iceland as the

terrain on the moon is similar. The gravity on Iceland was unfortunately our normal one as we found out when carrying

loads of 65lbs on 20 mile marches.

Marches

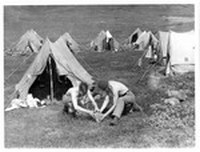

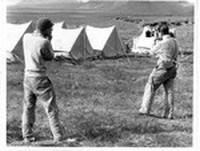

The trips we made from base camp in small groups were called marches, but we didn't actually march as we were carrying heavy rucksacks and the terrain was rough.(See photos below)We would rise about 6.30, breakfast, pack up the campsite and set off at 8.00, walk for 50 minutes then rest for 10 minutes until 12 when we would stop for an hours break to eat lunch. At 1 we would do 4 more 50 minute sessions and at 5 would pitch our tents and prepare our evening meal.

We slept two in a tent at base camp, quite comfortably with our personal gear, but to save weight on the march we took one tent for 5 people. They were wide enough to sleep sideways, so we slept like sardines, head to toe, in our sleeping bags .

On the Glacier

To give us some useful things to do instead of just tramping around, various groups were given specific tasks.

Dr. Ian Ashwell, a veteran of Iceland, working with the Meteorological Office, joined the party as a leader, but primarily he was there to do some research into the Icelandic weather. His major project was to take weather readings at base camp at the foot of the Langjokull glacier during the 6 weeks we were there and at three heights on the glacier itself during a 10 day period. The results were to be published and given to the Icelandic government as a courtesy for allowing to explore their country. I was assigned to the lower camp on the glacier.

Each camp was composed of a leader and 4 boys in one tent. We organised ourselves into 4 hour shifts and took hourly readings during the day and night.

To get on to the glacier we had sledges loaded with stores and equipment which had to be dragged across the very rocky terrain at the foot of the glacier and the melt water which ran off in many little streams. It was very hard work, I remember, and to add to our misery, it poured with rain which soaked through our clothing. When we finally set up the tent and crawled inside we were at the depths of despair which soon started to recede with a nice cup of hot cocoa. Major Douglas M.C, the leader of my tent, who was a veteran of the Malaya insurgency of the early 1950's, then produced a bottle of whisky which he announced he had brought for "medical emergencies". He had judged the situation perfectly and after a few sips and a sing-song we were all back in high spirits. In my diary for that day I wrote that I was fed-up and wished I hadn't come, but of course we were there specifically for a tough experience.

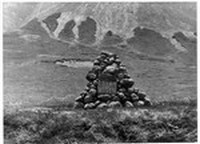

To link up the three camps, we paced out 1/4 mile markers. At each alternate one we built a snow cairn with aniline dye on it. On the others we placed an ablation stake and flag. This was to help the higher camps to come down in the event of really bad weather. Even though it was summer, blizzards were still possible on rare occasions. We experienced a blizzard on a later march.

Another task was to dig pits to be able to measure the snowfalls from previous years. The snow falls in winter, then in the summer the top surface will melt slightly, so by comparing the thickness of each layer, an idea of previous weather conditions going back for years can be recorded.

Sleeping on the ice was uncomfortable as we did not have the proper gear. Our sleeping beds were ex-army filled with kapok. We did not have air-beds either. My diary records the following: 'When I went to bed I wore all my clothes including hood up. I laid on one layer of sleeping bag. two layers of sheet, a groundsheet and a cape and still the cold came up from the snow. I wore no socks, but my feet were not cold. My sleeping bag was still wet at the bottom and the cover is soaked, but there is nothing to do about it. It is one of the things to try our patience.

After the first night of climbing in and out of a crowded tent every hour to take the met readings which disturbed the others, I came up with an idea. I dug an oblong hole about a meter deep, then using blocks of snow to raise the walls and the sledge as a roof, an ice cave was built. With a plywood biscuit box for a seat and another for a table I spent my shift with the primus stove on and a torch and a book. The other 2 camps built similar 'igloos'.

There were no latrines there so a 'number 2' was a novelty for us. It involved taking a shovel and walking a respectable distance from the tent, making a shallow hole above which one squatted. Very uncomfortable and no reading the newspaper either!

Although cold of course, being summertime the sun shone almost everyday. With the reflection off the snow, our faces soon developed nice brown tans. We were told not to shave, so after 10 days when we returned to base camp, with our fledgling beards and brown faces, we looked like veteran explorers.

Many thanks to Keith Moffatt, the son of expedition member John Moffatt, who contacted me and sent me his late father's photos shown here. Without them my narrative would be lifeless